Cotton Candy Worlds Evolve into Rock Candy Worlds

| Science

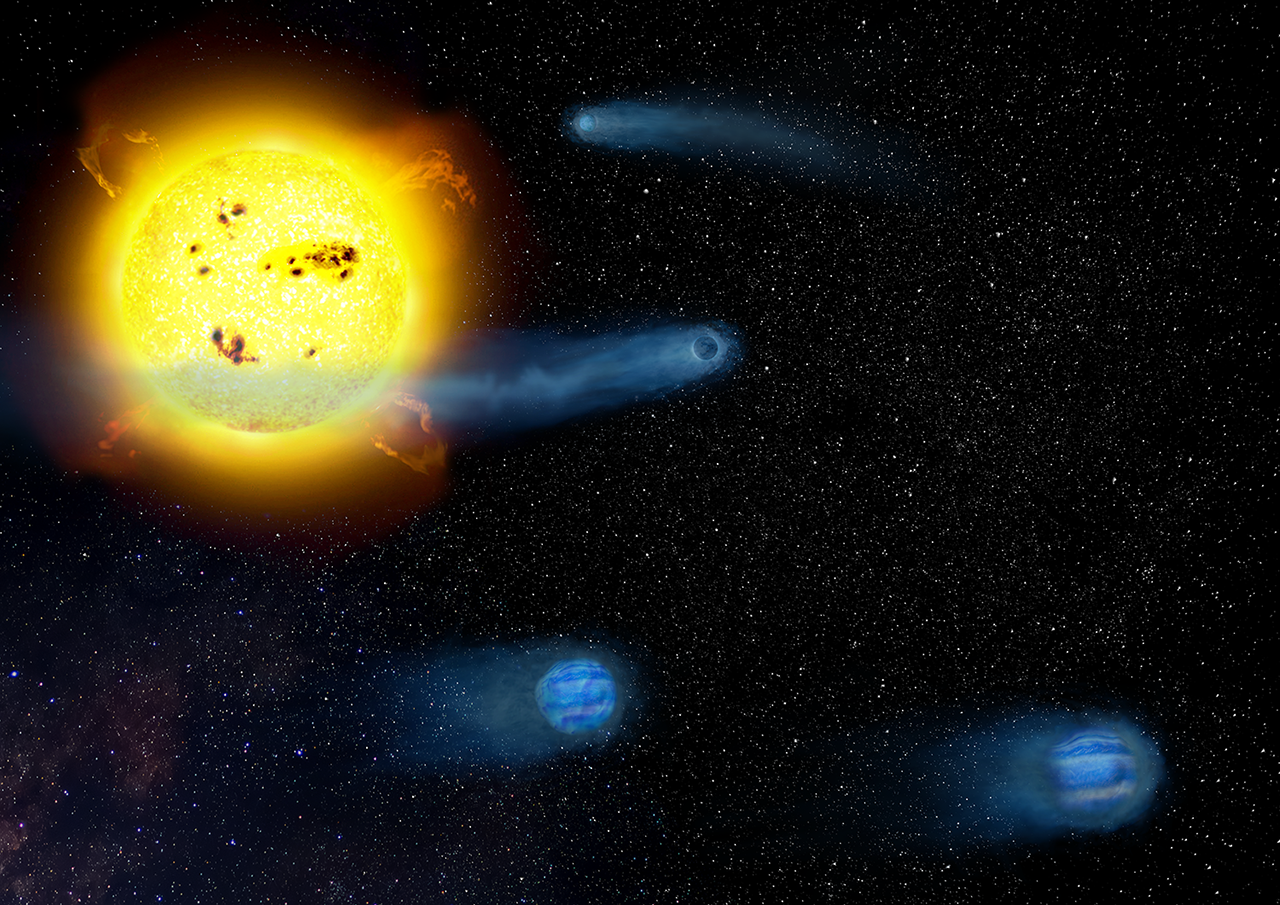

Using data spanning a decade taken by telescopes around the world and in space, including NAOJ’s 188-cm telescope in Okayama, astronomers have been able to weigh a quartet of baby planets. Even though the planets are currently large and puffy, like cotton candy, as they mature they will evolve into smaller, denser rocky worlds like Earth or small gaseous ‘sub-Neptune’ worlds.

One of the biggest recent surprises in astronomy is the discovery that most stars like the Sun harbor a planet between the size of Earth and Neptune at a distance from the star closer than Mercury’s orbit around the Sun. These ‘super-Earths’ and ‘sub-Neptunes’ are the most common type of planets known in the Galaxy. However, their formation has been shrouded in mystery. Now, an international team of astronomers has found a crucial missing link in the formation process. By weighing four newborn planets in the V1298 Tau system, the team captured a rare snapshot of the development of compact, multi-planet systems.

The study focused on V1298 Tau, a star located 352 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Taurus. V1298 Tau is only about 20 million years old, compared to our 4.5-billion-year-old Sun. Around this young, active star, four giant planets, all between the sizes of Neptune and Jupiter, have been observed in a fleeting and turbulent phase of rapid evolution. This system appears to be a progenitor of the type of compact, multi-planet systems found throughout the Galaxy.

The team used data taken over a decade by an arsenal of ground- and space-based telescopes to precisely measure when each planet passed in front of the star, an event known as a transit. By timing these transits, astronomers detected small variations in the planets' orbits. Their orbital configuration and gravity cause them to tug on each other, slightly speeding up or slowing down the timing of the transit. These tiny shifts in timing allowed the team to robustly measure the planets' masses for the first time. The planets, despite being 5 to 10 times the radius of Earth, were found to have masses of only 5 to 15 times that of our own world. This makes them incredibly low-density—more like planetary-sized cotton candy than Earth-like rock candy worlds.

This puffiness helps solve a long-standing puzzle in planet formation. A planet that simply forms and cools down over time would be much more compact. The puffiness indicates that these planets have already undergone a dramatic transformation, rapidly losing much of their original atmospheres and cooling. Now the planets are predicted to continue evolving, losing their atmospheres and shrinking significantly, transforming into the kinds of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes which are often observed.

The V1298 Tau system now serves as a crucial laboratory for understanding the origins of the most abundant planetary systems in the Milky Way, giving scientists an unprecedented glimpse into the turbulent and transformative lives of young worlds. Understanding systems like V1298 Tau may also help explain why our own Solar System lacks the super-Earths and sub-Neptunes that are so abundant elsewhere in the Galaxy.

Detailed Article(s)

Astronomers Find Missing Link to Galaxy’s Most Common Planets

Astrobiology Center

This article is including a link to a article for kids.

Cotton Candies Floating in Space?

Space Scoop | UNAWE

Space Scoop | UNAWE

The Universe Awareness website provides children through the world with fun, easy to understand news and educational materials about the Universe. These help kids understand the size and beauty of the Universe. The “Space Scoop” section of Universe Awareness contains articles written for kids explaining current astronomy news. A Space Scoop is available for this article.